Phulia Handloom Sarees

-

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /True Blue, Pure Cotton, ‘Phulia Saree’ in Indigo Blue

Rajesh Basak

Ready To ShipNo reviewsThis mesmerising hand-woven, pure-cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ comes all the way from Phulia village located in Nadia district of West Bengal. The vibrant...

View full detailsOriginal price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| / -

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /Vivid Blue, Pure Cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ in Navy Blue

Rajesh Basak

Ready To ShipNo reviewsThis vibrant hand-woven, pure-cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ comes all the way from Phulia village located in Nadia district of West Bengal. The aesthetics ...

View full detailsOriginal price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| / -

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /

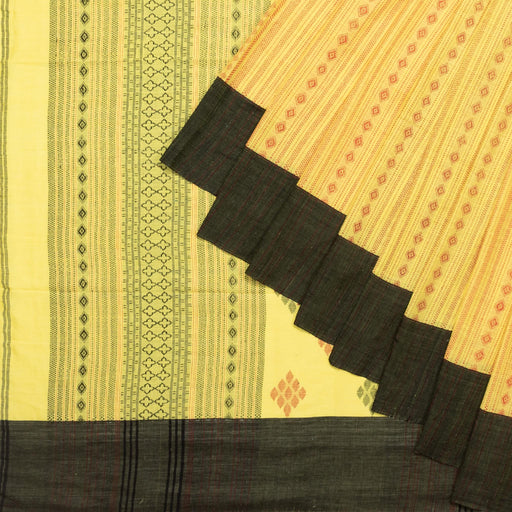

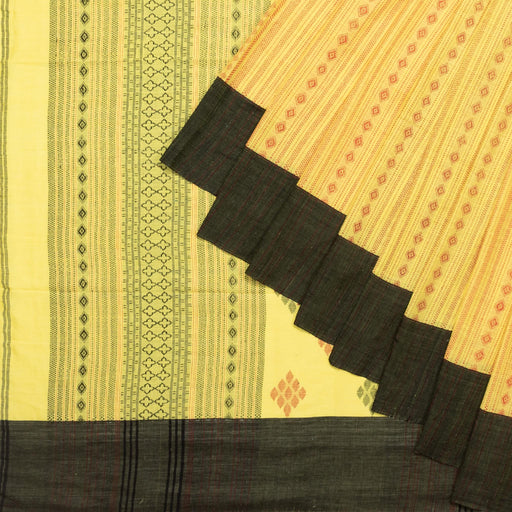

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /Subtle Sun, Pure Cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ in Yellow

Rajesh Basak

Ready To ShipNo reviewsThis ingenious hand-woven, pure-cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ comes all the way from Phulia village located in Nadia district of West Bengal. The pale yell...

View full detailsOriginal price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| / -

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /

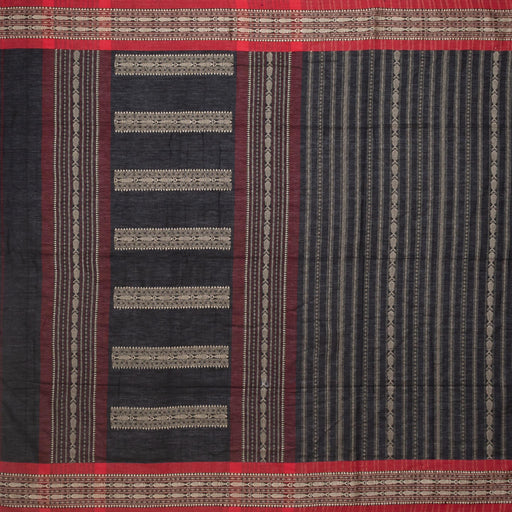

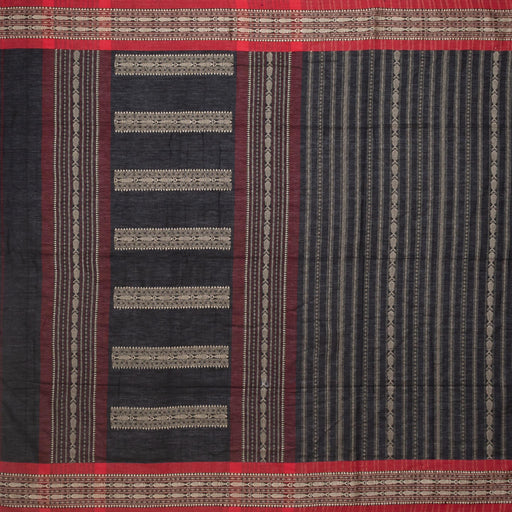

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /Royal Hues, Pure Cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ in Black and Red

Rajesh Basak

Ready To ShipNo reviewsThis opulent hand-woven, pure-cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ comes all the way from Phulia village located in Nadia district of West Bengal. This black drap...

View full detailsOriginal price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| / -

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /

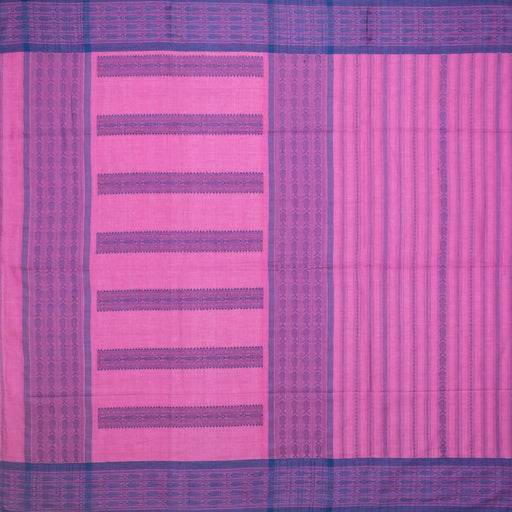

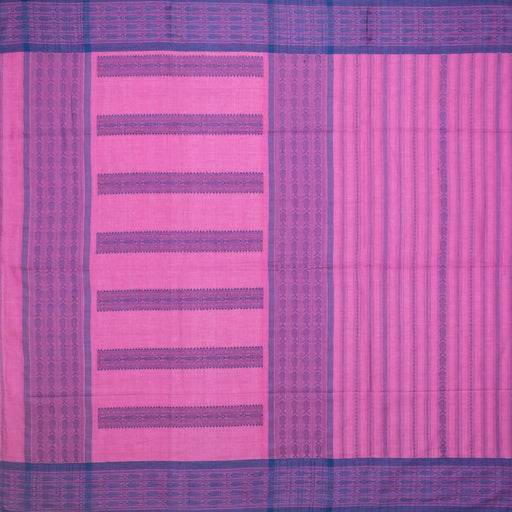

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /Lotus Bloom, Pure Cotton Pink ‘Phulia Saree’

Rajesh Basak

Ready To ShipNo reviewsThis breathtaking hand-woven, pure-cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ comes all the way from Phulia village located in Nadia district of West Bengal. The beauti...

View full detailsOriginal price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| / -

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /

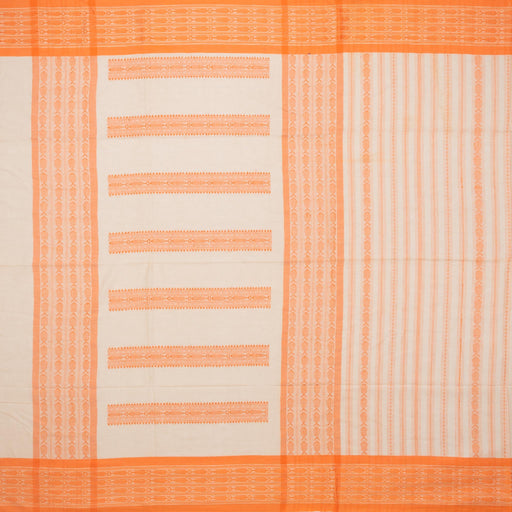

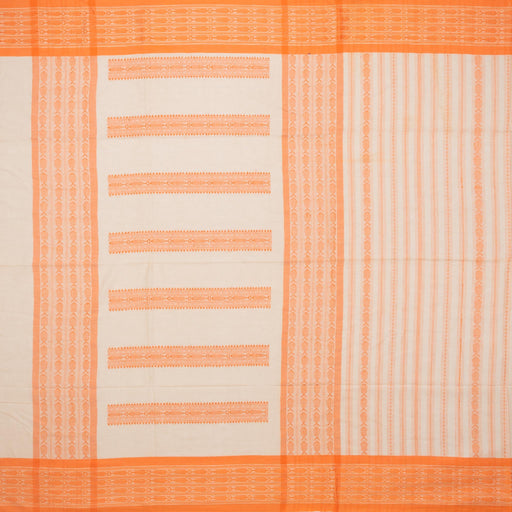

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /Orange spectrum, Pure Cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ in Off-white and Orange

Rajesh Basak

Ready To ShipNo reviewsThis dazzling hand-woven, pure-cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ comes all the way from Phulia village located in Nadia district of West Bengal. Adding vibranc...

View full detailsOriginal price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| / -

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /

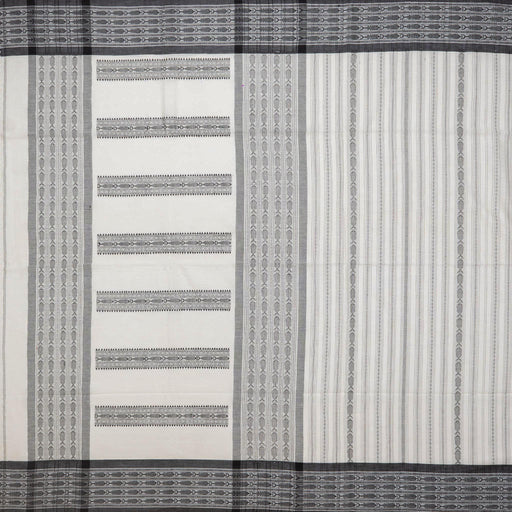

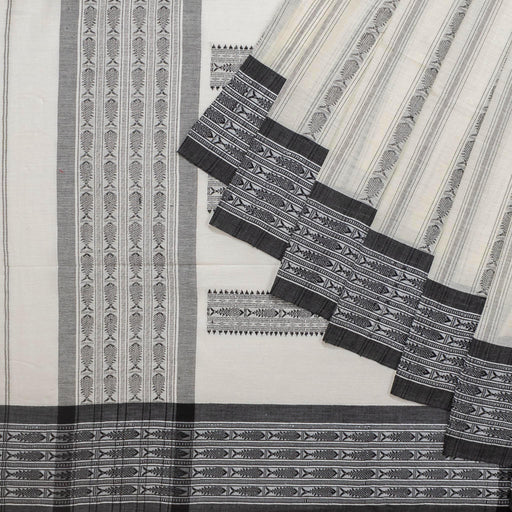

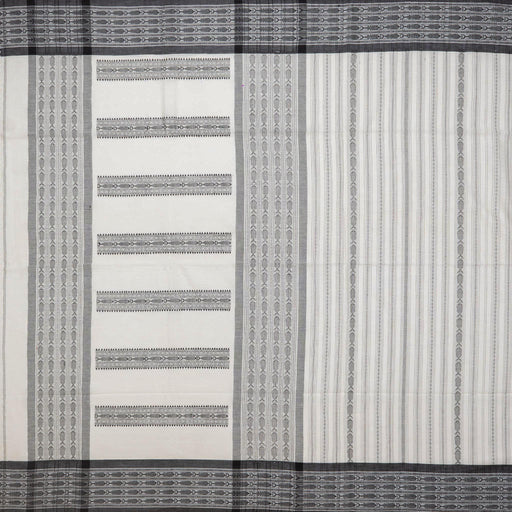

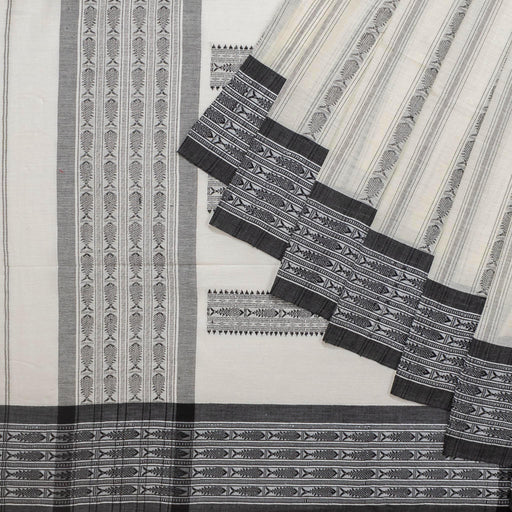

Original price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /Moonlit Elegance, Pure Cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ in Off-white and Black

Rajesh Basak

Ready To ShipNo reviewsThis elegant hand-woven, pure-cotton ‘Phulia Saree’ comes all the way from Phulia village located in Nadia district of West Bengal. The beauty of t...

View full detailsOriginal price ₹4,525.00 - Original price ₹4,525.00Original price ₹4,525.00₹4,675.00₹4,675.00 - ₹4,675.00Current price ₹4,675.00| /

Origin

Phulia, often spelt as Fulia, is a village in Nadia district of West Bengal. It has been home to weavers of traditional Bengali cotton sarees for decades. In the aftermath of the partition in 1947 and that of the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, Naida and the adjoining Bardhhaman district in West Bengal saw a huge influx of skilled weavers, who resettled in the region after migrating from Tangail district in Bangladesh. These weavers held expertise in hand-weaving ‘Tangail Sarees’ which bear similarities to the renowned Dhakai Jamdani sarees.

Over the years, Phulia has thrived as a hub of handloom weavers, who have stayed true to traditional practices while incorporating slight evolutionary changes to align better with market tastes and preferences. Today, a wide range of ‘Phulia Sarees’, in different materials and styles are hand-woven with finesse in this village. The offerings include ones ideal for daily wear as well as more plush ones, suitable for gifting and wearing on occasions like weddings.

Evolution

Tangail sarees are distinguished by generous use of scratch in their weaving process and the presence of Jamdani motifs all over the body. Over the last decade, weavers from Phulia have modified their approach. Understanding the changing market dynamics, use of starch in the weaving process has been drastically reduced or done away with altogether, making the sarees softer and more comfortable to drape.

Decorating the body of the saree with Jamdani Motifs can be an arduous task, so now weavers use a Jacquard loom to interweave beautiful patterns in the saree. Today, their offerings come in a wide variety of colours and designs. Fabric for the blouse is also included in the saree now. Apart from cotton, Phulia sarees are hand-woven using Chinese silk, matka silk and linen. Additionally, new products like yardage, scarves and stoles are also being woven.

The process

The first step, preceding the weaving process, involves thorough washing of the yarn and its de-gumming.

Thereafter, the yarn is dyed in a vat, squeezed to drain off the excess liquid and left to dry.

The yarn is then starched with rice-water. This stiffens it up, making it easier to set on a spinning wheel.

The starched yarn is placed on a wheel, which is rotated to transfer the yarn to small bobbins.

From bobbins, the yarn is transferred onto large drums. Starting from this stage, all steps are taken according to the planned design.

The bands of yarn are spaced on the drum in consonance with the envisioned design of the weave.

Next, the yarn is carefully measured and placed on the warp beam in accordance with the pattern sought out.

Finally, we arrive at the stage of drafting. The loom is set according to the desired weave design. The yarns are pulled through tiny metal rings to set the warp of the saree.

The yarns are then lifted according to the number of shafts required for the weave.

The warp beam is now set on the loom, moving closer to the culmination, the meticulously planned weaving process. One, that requires utmost precision to execute.

The weaver uses a shuttle to pass the weft yarns through the yarns of the warp, or the longitudinal yarn. With their feet they manipulate the warp. The intricate, fine interweaving of the warp and weft gives shape to the final weave yearned by the weaver.

Weaving complex designs

In Phulia, complex patterns with raised yarns are interwoven using the Jacquard loom. It involves the use of multiple punch cards laced together. Each row of punched holes of the cards strung together in accordance to the desired pattern corresponds to a row of the design in the weave.

Surviving against the odds

The handloom industry of Phulia is facing its own set of challenges such as competing with the might and cost efficiencies of power looms and usage of synthetic yarns.

Increasing rate of raw materials, low wages and rising imports of sarees from Bangladesh add to the list of woes of the weavers’ community in Phulia, which is the only place in India where traditional Tangail sarees continue to be handwoven.

Enabling better market access to the weavers and ensuring they receive fair remuneration for their skilfully designed handloom products is essential to ensure that this rich heritage continues to thrive.